Why should we care?

The location of district lines decide which voters vote for which representative. Changing the lines will change the relevant voters, and can change the identity, allegiance, and political priorities of a district’s representative, and of the legislative delegation as a whole.

Click on the wheel to see how.

American attempts to tailor district lines for political gain stretch back to the country’s very origin. Patrick Henry, who opposed the new Constitution, tried to draw district lines to deny a seat in the first Congress to James Madison, the Constitution’s primary author. Henry ensured that Madison’s district was drawn to include counties politically opposed to Madison. The attempt failed, and Madison was elected — but the American gerrymander had begun.

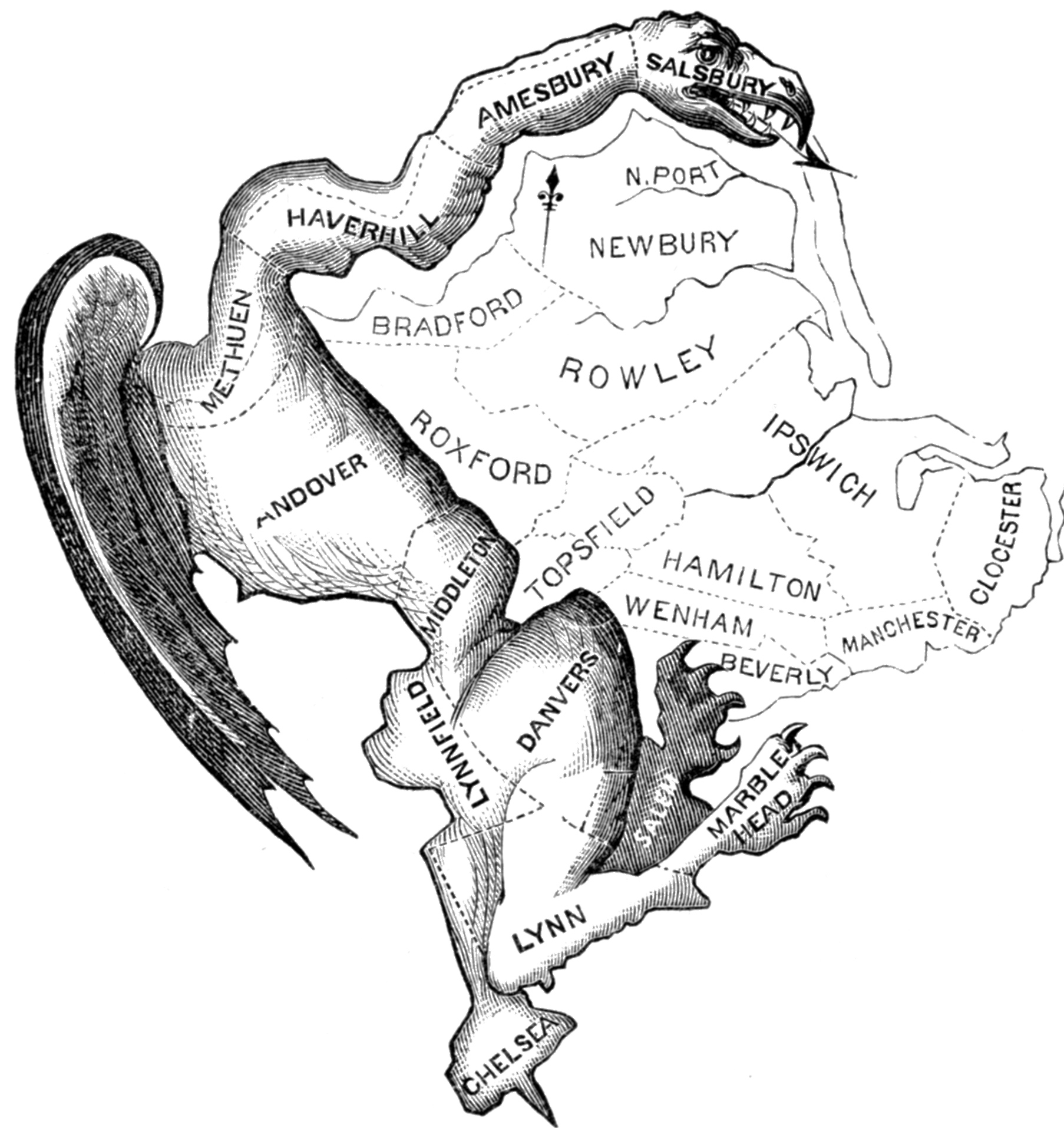

Ironically, the man who inspired the term “gerrymander” served under Madison, the practice’s first American target. Just a few months before Elbridge Gerry became Madison’s vice president, as the Democratic-Republican governor of Massachusetts, Gerry signed a redistricting plan that was thought to ensure his party’s domination of the Massachusetts state senate. An editorial artist added wings, claws, and the head of a particularly fierce-looking salamander creature to the outline of one particularly notable district grouping towns in the northeast of the state; the beast was dubbed the “Gerry-mander” in the press, and the practice of changing the district lines to affect political power has kept the name ever since.

It’s worth noting that the shape of the “Gerry-mander” isn’t that odd in the abstract. The district is just a collection of the towns ringing Essex County. The reason the editorial cartoonist gave it wings, claws, and a head isn’t really about how it looked, but what it was doing: trying to secure partisan victory in a way that opponents thought illegitimate. How a district looks is rarely a guide to whether it’s good or bad: there are “pretty” districts that give awful representation, and “ugly” districts that give wonderful representation.

In most states, the gerrymander is alive and well, doing bad things. Politicians still carve territory into districts for political gain, usually along partisan lines. This can lead to some serious consequences for the health of the democracy:

Locking up power

Until Proposition 11 was passed in 2008, California’s redistricting system was controlled by the state legislature. Under this system, after the 2000 census, the major political parties effectively decided to call a truce, and to keep the congressional incumbents of both parties safe from effective challenges. Many incumbents each paid a consultant at least $20,000 to have their districts custom-designed for safety. As one member of Congress explained: “Twenty thousand is nothing to keep your seat. I spend $2 million (campaigning) every year. If my colleagues are smart, they’ll pay their $20,000, and [our consultant] will draw the district they can win in. Those who have refused to pay? God help them.” In the next election, every single incumbent, Republican and Democrat, won by more than 20% . . . except for the one whose margin of victory was 19%.

Eliminating incumbents

After the 2000 elections in Virginia, the Republicans who controlled the redistricting process targeted Richard Cranwell, the Democratic leader in the state House of Delegates, who had represented his constituents for 29 years. They surgically carved his house out of the district he had represented, and placed it in the district of his 22-year colleague, Democrat Chip Woodrum. Woodrum’s district looked like it had a tiny grasping hand reaching out to grab Cranwell’s home. Rather than run against the hometown favorite in an unfamiliar district, Cranwell decided not to run for reelection.

And in New York, in 2011, the Democratic Speaker of the New York Assembly allegedly used the redistricting process to target a romantic rival, Republican and former Minority Whip Dan Burling. Speaker Sheldon Silver was allegedly having an affair with a member of the Assembly, and apparently discovered that Burling was also having an affair, with the same representative. (Despite circumstantial evidence produced in court, there have been some heated denials from the parties involved.) When it came time for redistricting, the district Burling had represented was shifted substantially west, to include a popular up-and-coming Republican mayor; Burling retired rather than face the primary challenge. Four years later, Silver was convicted on federal corruption charges.

Eliminating challengers

In the 2000 primary for an Illinois congressional seat, then-state Senator Barack Obama threw together a hasty campaign against a sympathetic incumbent, and won more than 30% of the vote. Though Obama lost, his campaign set the stage for a stronger showing in a potential rematch.

When Illinois redrew its districts, the state legislators deferred to incumbent members of Congress, including the incumbent whom Obama challenged. When the redistricting was done, the block around Obama’s home was carved out of the district (click here for the 2000 map, and here for the 2002 map, or click on the images to the right). Obama would have been forced to sell his home and move in order to live in the district where he had run 2 years before.

When Illinois redrew its districts, the state legislators deferred to incumbent members of Congress, including the incumbent whom Obama challenged. When the redistricting was done, the block around Obama’s home was carved out of the district (click here for the 2000 map, and here for the 2002 map, or click on the images to the right). Obama would have been forced to sell his home and move in order to live in the district where he had run 2 years before.

Extreme partisan gain

North Carolina is a deeply divided purple state: in 2008, the Presidential race split 50-50; in 2012, it split 51-49; in 2016, it split 52-48. But when the state legislature, unilaterally controlled by Republicans, sought to redraw congressional lines in 2016 after a court struck down an earlier plan, the committee chair said “I propose that we draw the maps to give a partisan advantage to 10 Republicans and 3 Democrats.” Why such a lopsided result? “[B]ecause I do not believe it’s possible to draw a map with 11 Republicans and 2 Democrats,” he said.

In Maryland in 2011, Democrats aimed in the opposite direction. The Democratic Governor — who drew the map that was then ratified by the Democratic legislature — testified that he “set out to draw the borders in a way that was favorable to the Democratic party.” And they were successful, lavishing particular attention on a district in western Maryland to ensure that Democrats won 7 of the state’s 8 congressional seats.

Diluting minority votes

After Democrats controlled Texas redistricting in the 1990s, Republicans took charge in 2003. The redistricting battles were so fierce that Democratic legislators actually fled to Oklahoma and New Mexico in an attempt to prevent the legislature from meeting to draw lines. (The Democrats hid out in Oklahoma in a Holiday Inn, under assumed names. A law student reviewed the episode in a paper, beginning: “Historically, there are many reasons why middle-aged men might sneak into a motel late at night. Until now, redistricting has not been one of them.”

When the lines were ultimately drawn, they moved about 100,000 Latino voters out of one district in order to protect an incumbent who was beginning to lose the support of the Latino population. Latinos had recently become the majority of the eligible population in the district, when they were replaced by voters more likely to support the incumbent. As the Supreme Court put it, “the State took away the Latinos’ opportunity because Latinos were about to exercise it.”

In 2011, Texas had another opportunity to redraw district lines. The legislature effectively did the same thing, in the same place, to the same Latino voters. “As it did in 2003, the Legislature . . . reconfigured the district to protect a Republican candidate who was not the Latino candidate of choice from the Latino voting majority in the district,” intentionally manipulating communities “to create the façade of a Latino district” that would not actually perform. A federal court found that “the Texas Legislature intentionally discriminated in 2011 [against Latino voters] in numerous and significant ways” . . . and found it increasingly likely that the Legislature would continue to find ways to defy the Constitution in the future.

Splitting communities

In 1992, race riots in Los Angeles took a heavy financial toll on businesses in many neighborhoods, including the area known as Koreatown. When residents of Koreatown appealed to their elected representatives for assistance with the cleanup and recovery effort, however, each of their purported representatives claimed that the area was really a part of some other official’s district. The redistricting map, it appeared, had fractured Koreatown — an area barely over one square mile — into four City Council districts and five state Assembly districts. As a result, no legislator felt responsible to the Asian-American community.

Fostering dysfunction

In many ways, because redistricting can have such a direct impact on incumbents’ electoral fortunes, it is among the most personal of issues for legislators, with every change in the lines a great favor or a piercing slight. Goodwill poisoned by the redistricting process can spill over into the entire rest of the legislative term. So it is disturbing, for example, when a federal judge quotes a Madison County, Illinois, committee chairman explaining to a colleague that “We are going to shove [the map] up your f—— a– and you are going to like it, and I’ll f— any Republican I can.”

Indeed, in Illinois, this sort of behavior seems well within the norm. In 1981, in a dispute over the handling of a redistricting plan, a legislator on the floor of the Statehouse charged the Senate President — whereupon a legislative colleague (and former Golden Gloves boxer) punched him in the face.